Cowboy Bebop has a phrase in its commercial bumpers: The work, which becomes a new genre itself, will be called Cowboy Bebop.

This phrase is pasted over the background of the opening sequence as well. Director Shinichiro Watanabe told Anime Invasion in 2003 it was a puffery line from the pitch document that an animator translated and added to the bumpers to give them some flair. Watanabe did not have grand aspirations of creating a new genre or a lucrative anime franchise; in fact, the production team torpedoed Sunrise’s sponsor deal with Bandai by designing spaceships that would not be good as toys or scale models. Watanabe planned the show to end with Vicious’ unambiguous death and Spike’s ambiguous collapse as insurance against being tied to the property for something like 720 episodes. He originally wanted to do one movie, but had to settle for 26 short films (and a feature-length film a few years later).

In the 20 years after Bebop’s debut, anime print magazines and online publications have hailed it as one of the best anime of all time. Rian Johnson, on his personal forum in 2006, said that his debut film Brick pulled inspiration from Cowboy Bebop. One user pointed out similarities in how the camera moves within scenes. Johnson said downthread that he showed Bebop to Matt O’Leary, who modeled his performance as The Brain on the show (he did not specify what O’Leary was modeling). Adult anime fans still recommend it to younger people looking for a way to get into anime; last month I told a group of teenagers that I had recently watched Cowboy Bebop, and each kid told me they had seen it too, and it was one of the best shows they’ve watched. I’d seen memes of the characters before I was challenged to watch Bebop:

And I’d seen the show satirized by real life:

While watching the show and taking notes, certain moments stuck out to me as possible points of reference for subsequent art with which I was familiar. But when I dug deeper on each of these reference sources, I started to doubt my perception. Was I imagining these connections to make the show feel more important? Is this like when you describe a friend as looking identical to a celebrity from memory, and then check your work later and discover they look nothing alike? I felt like Oedipa Maas looking for hidden messages in the logo of a regional parcel service. They’re just images, they’re not related! I will tell you how I think they’re related.

The first, and weakest one, is Saito Hajime from Fate/Grand Order, a gacha game popular in Japan. Every year the game adds characters based on members of the Shinsengumi, the Tokugawa shogunate’s special police force in the 1860s. Two years ago, the Japanese server added this guy:

Side by side, Spike and Saito look nothing alike. Spike’s hair is bigger and a different color; Saito has a worn face with sharper features; Spike never carried a sword, let alone two. But Saito’s spiky hair, his high collar, and his slightly ruffled dress shirt all look inspired by Spike. Saito is a professional killer, but he’s a flippant, easy-going jokester,

according to his translated profile on the F/GO Fandom Wiki. While it’s arguable that his described personality is a common trope in adventure stories, it’s similar to how I would describe Spike by the end of Bebop. I wouldn’t be surprised if the uncredited writers of his Shinsengumi event drew inspiration from Spike Spiegel for their image of Saito Hajime as a laid-back rogue.

While I was writing this section, a second design similarity occurred to me: F/GO’s Daybit Sem Void looks like Vicious:

Daybit is a mysterious villain from the later part of F/GO’s story. While he and Saito Hajime never cross paths, I can’t help but think Daybit’s design was inspired by Vicious. Daybit wears a dress shirt and tie under a vest, and he covers up with a shiny leather trench coat. His light-colored hair is long and loose, breaking into straight locks. Vicious looks similar, although he is wearing a full suit with vest under his trench coat, and his hair is platinum instead of blond. It seems to be a look popular among ultimate villains, as Daybit is the final enemy the player may have to face (his story chapter has not yet been announced on the Japanese server). Again, this kind of look might be common among a villain archetype or trope; take Sephiroth’s violently kakkoii style, which preceded Cowboy Bebop by a year. Sephiroth shares some key features between both characters, notably his long hair, black trench coat, and mysterious villain bullshittery.

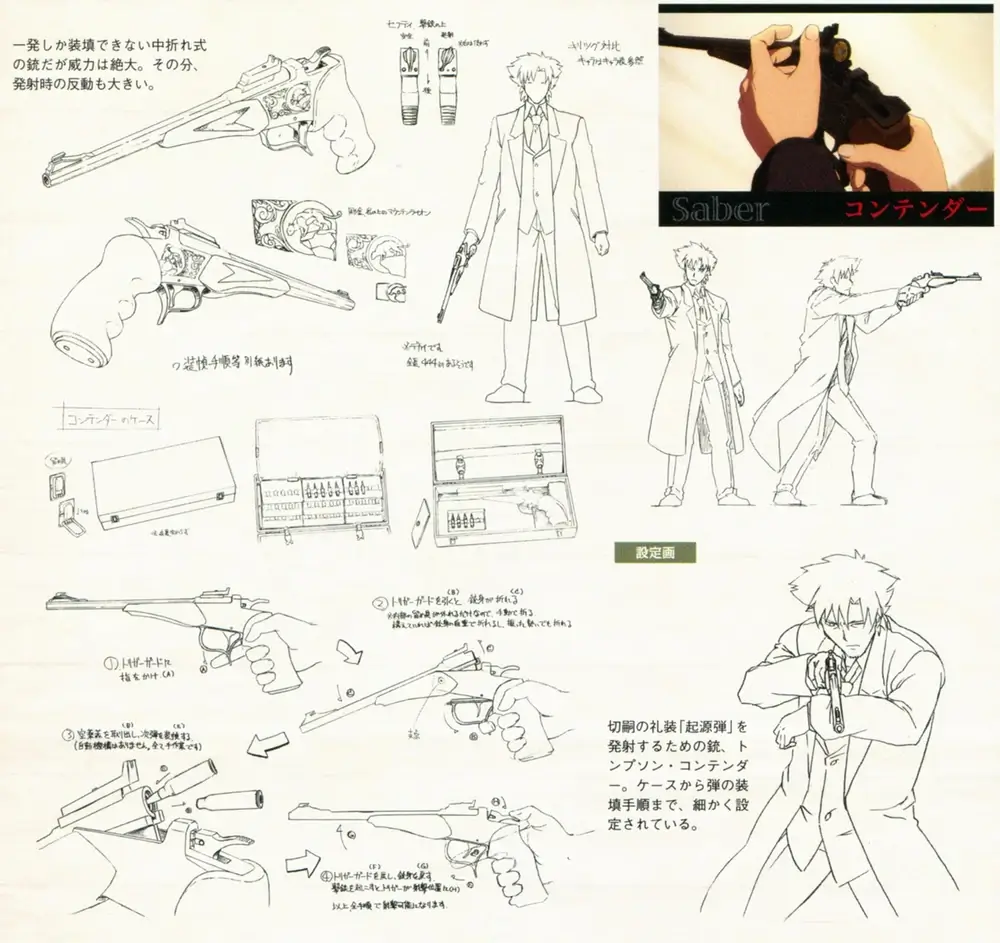

The second reference point is the Thompson Contender from “Sympathy for the Devil.” Spike and Jet cut a space gem into a bullet and jam it into a .308 Winchester cartridge. Then, to kill an 80-year-old child, Spike fires the Infinity Stone round out of a modified Thompson Contender and into the kid’s head, instantly aging him into a mummy. I’m being glib because the scene is preposterous, but in spirit it’s very similar to how Fate/Zero’s Kiritsugu Emiya deals with his problems. Kiritsugu is a professional wizard hunter who uses “origin rounds” to disable his targets’ magic abilities. Origin rounds are bullets made from Kiritsugu’s ribs chambered in .30-06 Springfield.

Spike’s gun is never identified as a Thompson Contender, and it has some mechanical details that deviate strongly from the Contender’s design, but the stylized grip and breech loading system are hallmarks of the Contender. Kiritsugu’s gun is identified several times as a Contender, and it looks like a stock model of the gun. Gen Urobuchi, the author of the original Fate/Zero novel, said he was inspired by John Woo’s 1993 film Hard Target, which features Lance Henriksen as a Contender-wielding villain. While that’s a likely source of inspiration, especially considering how often Kiritsugu fires his gun, Henriksen doesn’t have magic bullets designed to foil the supernatural powers of Jean-Claude Van Damme. Kiritsugu’s origin rounds appear to be an adaptation of Spike’s space gem bullet: a custom-crafted bullet fitted to a high-power wildcat cartridge, all designed to be fired from a Thompson Contender to sunder the one thing the target relies upon the most to enact their schemes. For Spike, it’s an ageless kid. For Kiritsugu, it’s wizards.

The third point of reference is hard to explain with words, so I’ll give some background and then a Youtube link. The Canadian techno band Purity Ring probably sampled part of “23 Hanashi,” the motif for Londes in “Brain Scratch.” I listened to both tracks like 50 times, then I overlaid them and tried my best to synchronize the beats I thought matched. In the end, both snippets are close but not exact. I looked for interviews with Purity Ring that would have mentioned influences for specific songs and found nothing. My best evidence is a video with each segment independently and then the segments overlapped. WARNING: I didn't equalize the volume before exporting, so it might be too loud for headphones.

It seems to me that Cowboy Bebop has had a profound effect on pop culture and on contemporary anime. Did the work become a new genre

? I don’t think so. Cowboy Bebop is firmly entrenched in cyberpunk tropes. While it does have some Western influences, particularly in its frontier-style depictions of Mars, the Trigun manga beat Bebop to the punch by about three years, and the biggest cyber-space-western since Bebop was Firefly, a 2002 American show canceled after 14 episodes. Cyber-western isn’t a good descriptor since the show’s Western elements are weaker than its cyberpunk and noir elements. Bebop had a more materialist read on the cyberpunk genre than its contemporaries, but it didn’t do anything radically different from what William Gibson did in 1984’s Neuromancer. I would consider Cowboy Bebop as a bonafide neo-noir story. It hits most of the major aspects of noir: dreamlike imagery and movement, surreal events and people, ambivalent morality, high contrast lighting and shading, and plenty of flashbacks and voiceovers. Its frequent violence pushes the show in the direction of neo-noir, which is difficult to define, even when starting from a broad definition of noir. Watanabe made an excellent cyberpunk noir, but he did not reinvent the genre, nor did he create a new genre entirely.